The recent execution by Indonesia of six people convicted of drug smuggling, include five foreign nationals, has focused international attention on the new president Joko Widodo, better known by his nickname ‘Jokowi’.

His refusal of clemency for Andrew Chan and Myuran Sukumaran led many Australians to petition the president directly.

It is surprising that Jokowi, famous for his down-to-earth and friendly demeanour, should take such a hardline on the issue of the death penalty. In the case of Chan and Sukumaran, the clear evidence of their rehabilitation has been completely dismissed.

One of the key political issues here concerns Jokowi himself: why is he doing this? A common answer is that it is about political tactics. In particular, it is argued that Jokowi wants to project the image of a strong leader who stands up for Indonesian interests against foreign pressure, and is decisive in his political judgements. This argument rests on the contrast between the president and his contender in last year’s election, Prabowo, who used his military background and authoritarian rhetoric to portray Jokowi as weak and indecisive.

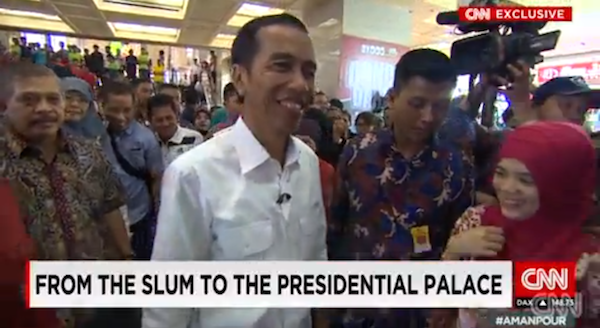

This ‘image of strength’ argument doesn’t hold up very well. The president’s popularity rests on his accessibility to the people, illustrated by his trademark impromptu visits (blusukan) that regularly make world news. The enthusiasm of ordinary people when they encounter Jokowi on the street suggests that they elected him exactly because he seemed a trustworthy, humble and accountable public servant, not an overweening autocrat.

Jokowi’s uncompromising attitude is a matter of conviction rather than political expediency. His policy on the execution of drug convicts is consistent with his ideological views as outlined in his Vision and Mission statement of May 2014.

This vision emphasises the paramount sovereignty of the nation-state. In that document, drug trafficking is lumped together with issues like official corruption and illegal fishing, under the heading “We Will Refuse to be a Weak State”.

Jokowi frames the problem of drugs in terms of state strength, both the power to protect citizens from the criminals importing drugs from overseas, and the power to exterminate the internal corruption that allows the drug trade to flourish.

Just weeks after the clemency issue became big news, five police officers were arrested for drug trafficking offences. The high media profile of such arrests of police and foreigners creates an aura of crisis in the state’s ability to protect its citizens, which compels the president to take any action necessary to restore state power.

Jokowi’s understanding of the dangers of drugs reveals his personal conservatism and the impact of the Suharto-era propaganda of his youth. By Jokowi’s reasoning, drugs are chiefly a moral danger. Drugs corrupt the personal character of young people, which leads to social disruption at the family and local level, which leads to instability in the nation.

This notion of “poor moral character” as the root cause of social problems has a long history in Indonesian politics, with its most articulate expression found in the Suharto government’s political indoctrination programs, which began in the early 1980s.

As an undergraduate student at the time, Jokowi would have been a primary target of these programs. By this philosophy, drug use needs not to be managed but to be eradicated, and the state has the ultimate responsibility and right to protect its citizens from this moral threat.

Jokowi can brook no compromise on the death penalty, because he sees clemency as the state retreating from its moral obligation to protect. He seems uninterested in harm minimisation approaches to drugs because his aim is a drug-free Indonesia, and he believes that a stronger state can achieve it.

It is somewhat surprising that he does not acknowledge the evidence that the death penalty is a poor deterrent, but his priority is ensuring the state is able to enforce the law in practice without corruption or foreign influence, rather than questioning the law’s provisions in principle. Jokowi’s commitment to action may have morphed into a reluctance to have a pragmatic debate about the death penalty’s effectiveness in achieving his goal.

If Jokowi’s moral instincts are making him obstinate, that is a big problem for a president whose survival depends, more than his predecessors, on his ability to be pragmatic in delivering tangible outcomes to his citizens.

The steeliness when he says “no compromise on clemency” is not theatre, but comes from his deep certainty that the state has the right to take life to protect the moral character of its citizens.

Jokowi’s ideological convictions may well have terrible consequences for Chan, Sukumaran and the dozens remaining on death row.

Donate To New Matilda

New Matilda is a small, independent media outlet. We survive through reader contributions, and never losing a lawsuit. If you got something from this article, giving something back helps us to continue speaking truth to power. Every little bit counts.