It’s a small sacrifice intended to recognise a far bigger one.

Every year, thousands of Australians pull themselves out of bed at dawn to brave the cold Canberra morning that heralds April 25th.

They arrive in darkness at the Australian War Memorial, one of the largest monuments to war in the world, to pay their respects to the servicemen and women who have contributed to Australia’s war time efforts. This year there are thousands more expected to honour 100 years of the Gallipoli legend.

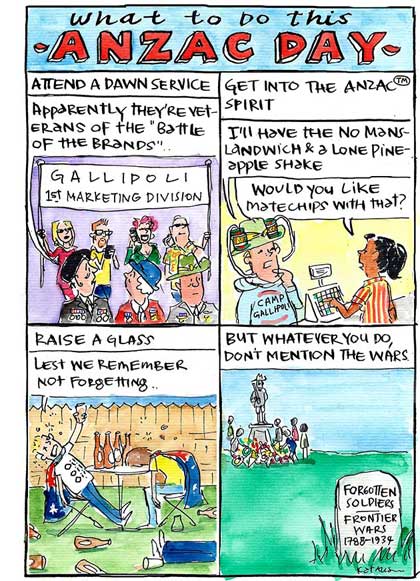

But there are few who sacrifice more time to remember those who were forgotten for so long. Aboriginal diggers were for a long time left out of ‘lest we forget’.

Every year, after the main dawn service, the Australian War Memorial advertises a separate ceremony honouring the Aboriginal contribution to war. It is run by the Aboriginal Torres Strait Islander Veterans and Services Association, and is intended to remember blackfellas who “served in the Australian forces since 1901,” the AWM website declares.

The ceremony is representative of a change – a growing willingness to remember the unique circumstances of black soldiers who were fighting for a country who refused them citizenship.

War changes people. But when Aboriginal soldiers returned they were confronted with the same old battles. They thought they had left behind the racism and discrimination when their black skin faded into the army green.

But when they returned many were refused entry into RSL clubs, and were unable to apply for land under soldier resettlement schemes. Some had their land stolen yet again when Aboriginal reserves were divided up for returned soldiers.

The Australian War Memorial for a long time was complicit in this amnesia, unwilling to recognise the black faces under the national caricature of the white Australian hero.

The Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander memorial was unofficial, and set up by volunteers. Even to this day, its positioning exists as a metaphor for Australia’s continual refusal to acknowledge black history. It lies a short, but steep walk up the rugged bush land of Mt Ainslie, well behind the impressive walls of the war memorial, with its ‘pool of remembrance’ and its gargoyles of Aboriginal men depicted alongside flora and fauna.

But while the rest of Australia is slowly beginning to acknowledge the contribution of black diggers with plays, memorials, ANZAC marches and ceremonies during Reconciliation Week, we still have several uncomfortable silences on April 25th.

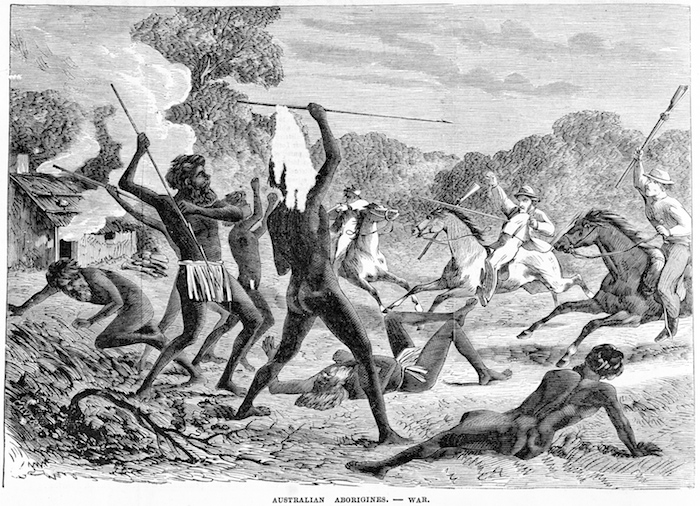

The most uncomfortable of which is the deafening silence around the most critical war in this country’s history – the Frontier Wars.

These conflicts were a far more accurate demonstration of our national character than Gallipoli.

There is no mention in the Australian War Memorial of the thousands of Aboriginal men, women and children who died defending their land from colonialists.

There is no separate memorial on ANZAC Parade to commemorate their loss, although there are memorials to other groups like nurses, and a planned memorial for war correspondents. In the lawns around the War Memorial, there are even statues dedicated to animals at war, but none for the first peoples, who fought valiantly for the land they had cared for meticulously for tens of thousands of years.

A growing body of work shows the battles at the beginning of colonisation were not ‘skermishes’ but warfare.

The most recent work – Forgotten Wars, by acclaimed historian Henry Reynolds – spells it out even more clearly, saying that “colonial historians placed frontier conflict in the mainstream of their narratives”.

“Many observers thought what was unfolding on the vast frontiers was a form of warfare. They said so many times over…. There seems not to have been any public debate about how appropriate the term was when applied to Australian history.”

There has been internal debate about whether the war memorial should recognise the Frontier Wars, and how the Australian War Memorial Act should be interpreted.

The memorial is set up as a corporation to “commemorate the sacrifice of those Australians who have died in war. Its mission is to assist Australians to remember, interpret and understand the Australian experience of war and its enduring impact on Australian society.”

The belief that Aboriginal tribes didn’t make an open declaration of war was used by conservatives to argue against a place for the Frontier Wars in the national monument.

Prime Minister John Howard said in 1998: “If you want to be legalistic about it, the state of war didn’t exist”. But an Australia War Memorial investigation in 1999 found that there was little doubt frontier conflicts were war or war-like operations, according to ABC’s 7:30 report in 2009.

The Australian War Memorial still refuses to acknowledge this.

In an address to the National Press Club in 2013, AWM head Dr Brendan Nelson said he didn’t believe the war memorial was the right place to tell the story of the frontier wars, instead stating the National Museum of Australia was more appropriate.

But if the AWM can commemorate colonial wars like the Boer War, and include an exhibition entitled ‘Soldiers of the Queen: Australia’s Colonial Military Heritage’, then why can’t it recognise the Frontier Wars?

In the Forgotten Wars, Reynolds makes a compelling case for recognition by linking frontier warfare to Australia’s overseas war contribution which was occurring at the same time.

The first names of the Roll of Honour at the Australian War Memorial are the nine men who died in Sudan, when NSW sent a contingent of 770 volunteers to help the British empire crush an Indigenous resistance in 1885.

But back in Australia, that same year “was probably the most violent” as invaders continued towards northern Australia across Kalkadoon and Karangura territories.

While the Australian War Memorial “commemorates the blundering attempt of NSW to go to war”, Mr Reynolds writes, “it totally ignores the very real, brutal war being fought at the same time across the northern third of the continent”.

But as the inevitable debates about what ANZAC Day means to each individual ramp up around the centenary, we must also think about who ANZAC Day has traditionally excluded.

While Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander servicemen and women are slowly receiving greater recognition, it means little without recognising the first wars of their ancestors.

Rather than Gallipoli, it is these wars which are characteristic of our national character and where we are as a country today. The enduring silence around the tens of thousands of black deaths demonstrates that Australia did not come of age on a Turkey battleground. Our failure to address our colonial killing times points to the fact we have never grown up.

The theft of Aboriginal land, so connected to identity, health and wellbeing, occurred then, and it is still occurring now, in the form of policies like the potential closure of up to 150 remote Aboriginal communities, the NT intervention and assaults on the NT Aboriginal Land Rights Act, the winding back of heritage legislation, and the trajectory of the land rights movement.

Our refusal to remember the past battles of warriors who fought long and hard for their land against a foreign invader helps wash away shameful memories on a day when we are encouraged to think positively about Australia’s contribution to war.

As we march alongside ANZAC Parade on Saturday, who wants a reminder of that past assault on land?

Who wants a reminder of the war where the majority side, ‘white Australia’s side’, is undoubtedly in the wrong even if, by its own reckoning, it was victorious?

Who wants a reminder of the thousands of Aboriginal men and women whose blood was shed so Australia can have the type of prosperity that allows the building of a multi-million dollar national monument to war?

Who wants a reminder of a people who fought for land they had existed on for tens of thousands of years, not a mere 200?

The Australian War Memorial refused to remember the people who fought for ‘country’, not ‘Australia’. But that doesn’t mean we shouldn’t.

* New Matilda is a small, independent Australian media outlet. We rely almost entirely on reader subscriptions for our survival. If you would like to help us keep reporting, you can subscribe here. Or you can help us by sharing this story on social media (click on the links below).

Donate To New Matilda

New Matilda is a small, independent media outlet. We survive through reader contributions, and never losing a lawsuit. If you got something from this article, giving something back helps us to continue speaking truth to power. Every little bit counts.